EDU 605: DI Blog

Unit 1 Blog: What is Differentiated Instruction?

Reflection

Creating a mind map to outline the key concepts of Differentiated Instruction proved to be a valuable exercise. Initially, it took a few minutes to jot down ideas, but the process became more manageable as I reflected on my daily one-on-one interactions with my homeschooled students. In her YouTube video, Tomlinson (2012) states, "Differentiated Instruction is teaching with students in mind," which is precisely what I strive to do regularly with my students. In implementing differentiated instruction, I utilize various strategies, such as personalized learning plans tailored to my children's strengths, weaknesses, interests, and learning preferences. My methods include flexible scheduling and diverse instructional materials like books, videos, hands-on activities, and online tools to cater to their learning styles. Additionally, I incorporate personalized projects aligned with my children's interests and abilities to allow them to explore topics they are passionate about in-depth, meeting their diverse learning needs.

Tomlinson (2001) states, "A teacher does not seek or follow a recipe for differentiation, but rather combines what she can learn about differentiation from a range of sources to her own professional instincts and knowledge base to do whatever it takes to reach out to each learner" (p. 7). As a homeschool educator, I adhere to the pedagogical approach rooted in the principles of differentiated instruction. This approach has proven to yield remarkable results in cultivating a dynamic and engaging educational environment that fosters intrinsic motivation and deep understanding among my children.

Although I do not have colleagues as a homeschool educator, if I were to explain differentiated instruction to an individual, I would describe it as an approach that acknowledges and embraces the various learning needs and preferences of students in the learning environment and involves adjusting teaching methods, materials, and assessments to accommodate individual learners' abilities, interests, and learning styles. By differentiating instruction, we aim to provide all students with meaningful learning experiences tailored to their specific requirements, enabling them to thrive academically. In addressing learners, I would define differentiated instruction by emphasizing that it's about ensuring each student can learn in a way that suits them best. Since everyone learns differently, some may prefer reading while others enjoy hands-on activities, and I would adapt my teaching methods to suit their unique learning styles.

Reference

Tomlinson, C. A. (2001). How to differentiate instruction in mixed-ability classrooms. Alexandria, Va: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development

Tomlinson, C.A. (2012, July 10). What is Differentiated Instructions?

Unit 2 Blog: Analyzing & Evaluating a Research Article

As a homeschool educator, an essential aspect of my teaching practice involves child-centered individualized instruction. This approach customizes the learning experience for each student by tailoring instruction, content, and pace to address their unique learning requirements. By offering personalized support and adjusting teaching strategies to align with their abilities, interests, and preferred learning styles, I aim to facilitate each child's success. Employing developmentally appropriate practices, I provide age-appropriate experiences, materials, guidance, and assistance corresponding to my children's developmental stage. Gronlund (2016) states, "Individualization is important because each child has special needs, interests, talents, personality traits, and learning styles" (p. 12).

The purpose of the article "Assessing Individualized Instruction In The Classroom: Comparing Teacher, Student, and Oberserver Perspectives is to address the measurement of individualized instruction in the context of regular classroom instruction, explicitly focusing on German third-grade reading lessons. The study assessed instructional practices related to Individualization by collecting self-report data from students and their teachers and through live observations. The argument made by the author revolves around the importance of evaluating individualized instruction in teaching quality. The author emphasizes the need to consider diverse perspectives, including those of students, teachers, and observers, to understand the effectiveness of individualized instruction practices.

The aim was to investigate the reliability of these various methods of measuring individualized practices and determine their degree of agreement. The findings indicated that all three approaches provided reliable indicators of individualized practices, but there needed to be more consistency in the level of agreement among students, teachers, and observers. The article highlighted significant agreement between students and observers but not with teachers' self-reports. It also noted that student and teacher ratings correlated more closely when teachers' measures accounted for response tendencies.

The parameters for finding the relevant research cited in this article included keywords such as individualized instruction, individualized instruction in the classroom, classroom instruction, and individualized teaching. The parameters for the literature review made sense as they focused on investigating individualized instruction in the learning environment and assessing its effects on learning outcomes. One potential flaw in the text/study is that it presents a one-sided view of the reliability of different measurement approaches. While it discusses the advantages of classroom observations and student self-reports, it focuses less on these methods' potential limitations and challenges. For example, classroom observations may be influenced by observer bias, limited observation timeframes, and the subjective interpretation of behaviors.

Similarly, student self-reports may be subject to social desirability bias and varying levels of student engagement or motivation in providing feedback. Additionally, the text mentions that younger children might have difficulty identifying and differentiating between pedagogical constructs (Tetzlaff et al., 2022, para 10), which could affect the reliability of student ratings. It would be beneficial to delve further into how age and developmental factors can impact the accuracy and reliability of student self-reports in evaluating instructional processes.

The research questions outlined in the text are as follows:

1) Can student reports, teacher reports, and live observations reliably evaluate the occurrence of specific instructional practices aimed at Individualization?

2) Do the evaluations of individualized task assignments from these perspectives correlate?

3) Does the type of self-report measure used for the teacher perspective, whether trait-based or retrospective, impact its agreement with the other perspectives?

These questions are asked to investigate the reliability of different assessment methods in measuring individualized instruction in the classroom, explore the extent of agreement or discrepancies between the perspectives of students, teachers, and observers, and understand how the framing of self-report measures for teachers may influence their reported behavior compared to other perspectives. The aim is to gain insights into the assessment and implementation of individualized instruction practices in educational settings, mainly focusing on individualized task assignments as a key instructional strategy for addressing learner variability.

The author makes several arguments based on the research. The author argues that assessing specific instructional practices related to Individualization in teaching quality is essential. The author suggests that using multiple perspectives, such as student reports, teacher reports, and live observations, can provide a more comprehensive evaluation of individualized instruction. The author points out that there may be discrepancies between how teachers perceive their individualized instruction and how students perceive it, highlighting the importance of understanding and addressing these differences. The author emphasizes the need for further research to explore the agreement or discrepancies between different perspectives and to investigate how the framing of self-report measures for teachers may impact their reported behavior.

The participants in the research mentioned are:

- Students: The text refers to students' perspectives on individualized instruction.

- Teachers: The research involves teachers responsible for implementing individualized instruction strategies and providing self-reports on their teaching practices.

- Observers: The text mentions live observations, suggesting the presence of observers who are assessing classroom instruction to provide an external perspective on individualized teaching practices.

The theoretical framework used by the author centers around the evaluation of individualized instruction in teaching quality. The author emphasizes the importance of understanding individualized instruction practices from multiple perspectives, including those of students, teachers, and observers. This approach aligns with theoretical frameworks commonly used in educational research, such as constructivism or sociocultural theory, stressing the importance of considering diverse viewpoints to understand teaching and learning processes comprehensively. Sparani (2013) states, "Constructivism can be defined as a philosophy of learning founded on the premise that, by reflecting on our experiences, we construct our own understanding of the world we live in" (p. 13).

The focus on assessing instructional practices related to Individualization indicates that the author is drawing on frameworks emphasizing personalized learning, student-centered approaches, and effective teaching strategies tailored to individual student needs. Some suggestions for further research could include exploring specific aspects of individualized instruction not addressed in the study, conducting longitudinal studies to assess the long-term effects, and examining the role of technology in facilitating individualized instruction.

References

Gronlund, G., (2016). Individualized Child-Focused Curriculum: A Differentiated Approach.

Sparapani, E.F., (2013). Differentiated Instruction: Content Area Applications and Other Considerations for Teaching in Grades 5-12 in the Twenty-First Century.

Tetzlaff, L., Hartmann, U., Dumont, H., Brod, G. (2022). Assessing Individualized Instruction In The Classroom: Comparing Teacher, Student, and Observer Perspectives. 82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2022.101655

Unit 3 Blog: Beliefs of differentiation

Differentiated instruction is an approach that recognizes the diverse learning abilities of students in the classroom. As an educator, I firmly believe in the power of differentiated instruction to cater to the individual needs of learners and promote inclusive learning environments. By tailoring lesson plans, activities, and assessments to meet the varied needs of students, differentiated instruction enables me to address skill gaps, enhance student engagement, and ultimately improve overall learning outcomes. I believe that differentiated instruction is a pedagogical approach essential for meeting students' diverse learning styles, abilities, and interests in the modern classroom. To support this belief, I offer the following facts, examples, and ideas:

Student-Centered Approach: Differentiated instruction places students at the center of the learning process by recognizing and accommodating their unique learning profiles. By incorporating various learning modalities, interests, and readiness levels into lesson planning, educators can create a more engaging and effective learning experience for all students. Sparapani (2013) stated, "Student-centered instruction is differentiated and focused at the ability levels of the learners. It attempts to nurture the whole child, mind, body, and spirit" (p. 6).

Research-Based Evidence: Studies have shown that implementing differentiated instruction increases student achievement, engagement, and success. For example, Huebner (2010) stated, "A three-year research study conducted by Canadian scholars found that differentiated instruction consistently yielded positive results across a broad range of targeted groups. The study revealed that students with mild or severe disability received more benefits from differentiated and intensive support compared with the general student population (p. 79).

Flexibility and Adaptability: One of the key strengths of differentiated instruction is its flexibility. Teachers can adapt their teaching methods, materials, and assessments based on ongoing formative assessments and student feedback. This allows for real-time adjustments to ensure that students are supported in reaching their full potential.

Regarding Tomlinson's idea to minimize noise in the classroom, I believe that implementing strategies to manage noise levels is crucial for creating a conducive learning environment for all students. To support this belief, I offer the following insights:

In her book "How to Differentiate Instruction in Mixed Ability Classrooms," Tomlinson emphasizes the importance of addressing noise levels to prevent them from becoming oppressive or distracting. Educators can cultivate a respectful and focused classroom atmosphere by establishing clear expectations from the beginning of the school year and working collaboratively with students. Tomlinson suggests teaching students to work with their peers quietly by modeling and reinforcing appropriate behavior, such as whispering or speaking softly during group activities (Tomlinson (2001) p. 36). Visual cues like turning the lights on and off quickly can gently remind students to lower their conversation levels and focus on the task at hand. Furthermore, Tomlinson recommends assigning a student in each group to serve as a noise monitor, responsible for monitoring the noise level within the group and gently reminding peers to speak softly when necessary. This practice empowers students to take ownership of their learning environment and helps create a more inclusive space for learners who may be particularly sensitive to noise distractions. By implementing these strategies advocated by Tomlinson, educators can proactively address noise disruptions in the classroom, promote student engagement, and provide an optimal learning environment that caters to the diverse needs of all learners.

References

Huebner, T.A., (2010). What Research Says About Differentiated Instruction. Educational Leadership. 6(5), 79-81.

Sparapani, E. F. (2013). Differentiated Instruction: Content Area Applications and Other Considerations for Teaching in Grades 5-12 in the Twenty-First Century

Tomlinson, C.A., (2001). How to Differentiate Instruction in Mixed Ability Classrooms, 2nd edition.

Unit 4 Blog: Differentiated Instruction Stragey

Because homeschool educators have the flexibility to work with multiage learners in co-op environments, they often find themselves in unique situations. Collaborating with other parents and sharing teaching responsibilities for students of different ages is common among homeschool educators. As I prepare to teach a group of multiage homeschool learners in a co-op setting next school year, I am eager to enhance my understanding of differentiation for students at various developmental stages. That is why I selected this video on Multiage Differentiated Instruction and Grouping.

Multiage differentiated instruction and grouping involve organizing students of different ages, typically within a range of one to three grade levels, in the same classroom/environment. This approach allows for personalized learning experiences that meet the diverse needs of students while promoting collaboration, social development, and academic growth. As stated in the video, "The key component to multiage is knowing the developmental levels of students versus the grade level" (MultiageLearning, 2012). From the video, I learned that grouping students with various learning styles can be beneficial as the learners can get enriched, rewarding experiences. I also learned that "multiage allows for seamless inclusion of special education students into the classroom" (MultiageLearning, 2012).

When applied to young children in the preschool to the 4th-grade range, multiage differentiated instruction and grouping offer several benefits:

Social and Emotional Development: Young children benefit from interacting with peers of different ages, fostering social skills, empathy, and cooperation. In a multiage setting, older students can serve as mentors and role models for younger ones, creating a supportive and inclusive learning environment.

Individualized Instruction: Multiage grouping enables teachers to better tailor instruction to meet students' varying academic abilities and learning styles. Teachers can provide differentiated activities and assignments that cater to each child's strengths and growth areas, fostering a more personalized learning experience. With that said, it is essential that teachers observe and assess learners to understand their progress and to identify strengths and weaknesses, allowing them to provide targeted support and interventions. "Teachers should observe students working individually, in small groups, and in the class as a whole with the intent to study factors that facilitate or impede progress for individuals and for the group as a whole" (Tomlinson, 2006, p. 47).

Continuous Progression: Children can progress independently without being confined to a strict grade-level curriculum in a multiage setting. This flexibility allows students to advance in subjects where they excel while receiving additional support in areas where they need more assistance, promoting continuous academic growth.

Peer Learning: Young children learn from observing and interacting with their peers. In a multiage classroom, students can engage in peer teaching and learning, where older students can help younger ones grasp concepts and skills. This collaborative approach not only enhances academic understanding but also strengthens relationships among students. "Multi-age classrooms allow greater opportunities for peer learning and collaboration. Older students can hold mentor roles for younger classmates, while younger students can observe and learn from the experience of others"(Multi-Age Classrooms - Primer Microschools, n.d.).

Reduced Stigma: In a multiage setting, there is less emphasis on grade-level distinctions, which can help reduce the stigma associated with being placed in a particular grade or ability group. Students are valued for their contributions and growth, fostering a positive and inclusive learning culture.

By leveraging multiage differentiated instruction and grouping, young children can experience a more holistic, personalized, and supportive educational environment that promotes social, emotional, and academic development in a well-rounded manner. I plan on using the multiage strategy by creating flexible groups based on learners' abilities, interests, and learning styles rather than strictly by age. I will encourage peer tutoring within the multiage group, where older students can help younger ones and vice versa. I will also implement project-based learning activities that allow students to collaborate on meaningful projects. Projects will be tailored to challenge students at varying levels and promote teamwork. The goal is to foster a supportive and inclusive learning environment where all learners feel valued, respected, and encouraged to take academic risks, celebrate the diversity within the multiage group, and promote a culture of collaboration and mutual support. By implementing these strategies, I can effectively differentiate instruction for learners of multiple ages, catering to their needs and fostering positive and engaging learning experiences.

References

MultiageLearning, (2012). Multiage-Differentiated Instruction and Grouping. https://youtu.be/I_9YeTIF_-4?si=nQXluM1tXHTkZOfF

Multi-age Classrooms - Primer Microschools. (n.d.). https://primer.com/resources/multi-age-classrooms

Tomlinson, C.A., McTighe, J., (2006). Integrating Differentiated Instruction and Understanding by Design : Connecting Content and Kids.

Unit 5 Blog: Multiple Intelligences

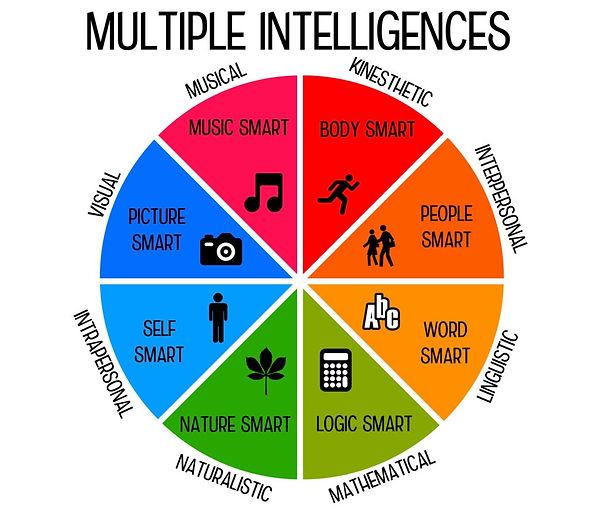

In a homeschool context, Gardner's Theory of Multiple Intelligences can be crucial in understanding and catering to individual students' diverse learning styles and strengths. This theory puts in place multiple types of intelligence, including linguistic, logical-mathematical, spatial, bodily-kinesthetic, musical, interpersonal, intrapersonal, and naturalistic intelligence. By recognizing and tapping into these different intelligences, a homeschool educator can personalize instruction better to suit each student's unique needs and preferences. "Gardner's Theory of Multiple Intelligences advocated that students could learn and display knowledge in multiple ways, according to their developed strengths. Gardner's concept purported that knowledge could be displayed in multiple ways- different "ways of knowing": verbal/linguistic, logical/mathematical, visual/spatial, musical/rhythmic, bodily/kinesthetic, naturalistic, interpersonal, and intrapersonal. MI provides a viable way to differentiate instruction so that a teacher can reach more students more of the time" (Gray & Waggoner, (2002).

When integrating Gardner's Theory of Multiple Intelligences with the 4MAT model, the emphasis on addressing various learning styles aligns well with differentiated instruction. McCarthy (2010) stated, "4MAT is about the interplay in how people perceive and process. Individuals perceive in two ways: Experiencing and Conceptualizing and process in two ways: Reflecting and Acting" (Aboutlearning4MAT). The 4MAT model, which is based on addressing different learning preferences through its four quadrants - why, what, how, and what if - can be enhanced by incorporating activities and assessments that target the different intelligences identified by Gardner. For example, students with linguistic intelligence may excel in reading, writing, and verbal communication activities. Gardner believed "that we all possess at least seven intelligence areas or seven ways of knowing" (Rule & Lord, (2003).

In the "what" quadrant of the 4MAT model, educators can provide reading assignments, writing tasks, and discussions to engage these students effectively. Students with strong spatial intelligence may prefer visual representations and hands-on activities. In the "how" quadrant, incorporating visual aids, diagrams, and project-based learning opportunities can cater to their strengths.

Incorporating music, rhythm, or mnemonic devices for students with musical intelligence can enhance their learning experience in the "what if" quadrant, encouraging creativity and exploration. By integrating Gardner's Theory of Multiple Intelligences with the 4MAT model in my homeschooling context, I can create a more inclusive and engaging learning environment that caters to my learners' diverse strengths and preferences. This approach promotes personalized learning experiences that foster academic success and student well-being.

References

Gray, K. C., & Waggoner, J. E. (2002). Multiple intelligences meet Bloom's taxonomy. Kappa Delta Pi Record, 38(4), 184–187.

McCarthy, B., (2010). Introduction to 4MAT by Bernice McCarthy. https://youtu.be/cpqQ5wUXph4?si=Ymfp8CrrRc_-oimh

Rule, A. C., & Lord, L. H. (Eds.). (2003). Activities for differentiated instruction addressing all levels of Bloom's taxonomy and eight multiple intelligences.

Unit 6 Blog: Differentiating Process, Product, and Content

As a homeschool educator, I am committed to providing my students with personalized and inclusive learning experiences. To achieve this, I implement differentiation strategies that cater to each learner's diverse needs and interests. By focusing on adapting the process, product, and content of instruction, I create a dynamic educational environment that nurtures growth and fosters success for all students.

Differentiated instruction is "teaching with the child in mind" (Casteneda). "Process means sense-making or, just as it sounds, the opportunity for learners to process the content or ideas and skills to which they have been introduced" (Tomlinson (2001), p. 79).

In differentiating the process for various subjects, such as science, I engage students through multiple avenues. For instance, during our unit study on caterpillars, I had set up various books about caterpillars and butterflies, displayed photos of caterpillars and butterflies at the easel with multiple colors of paint, had art materials available such as egg cartons, pipe cleaners, glue, scissors, tissue paper, pompoms, and more for the children to create their own caterpillars or butterflies, and had set up a mini butterfly garden with live caterpillars in our learning environment. Some students enjoyed closely observing the caterpillars with a magnifying glass, while others preferred drawing or labeling the different stages of metamorphosis. By providing these options, I cater to different learning preferences and styles, ensuring all students can participate meaningfully.

Moreover, when differentiating the product, particularly in subjects like Social Studies, I offered my learners choices in how they showcase their understanding. For example, during Hispanic Heritage Month, students had the option to create traditional Peruvian crafts, dress up in Peruvian clothing, prepare simple Peruvian recipes with a Peruvian chef, and learn basic words in Spanish. This approach allowed students to express their comprehension of the topic differently based on their interests and strengths.

Lastly, in differentiating learning activities for subject topics like Transportation, such as studying modes of transportation and vehicles, I provided a variety of engaging activities to cater to the needs of my learners. For example, I created a transportation-themed play area with toy vehicles and road signs, displayed transportation-theme pictures through the environment, and took transportation theme field trips such as riding on the city trolley, visiting the local train station, fire station, harbor marina, autobody shop, and built a car using cardboards and art materials during our unit study. Some students enjoyed building vehicles using Legos, while others preferred sorting pictures of different modes of transportation. This mix of hands-on play, visual aids, and construction activities ensures that students can explore the topic in ways that are most meaningful and enjoyable to them.

In conclusion, differentiated instruction is vital in creating a personalized and inclusive learning environment for students. By focusing on adapting the process, product, and content of instruction, educators can cater to diverse needs and interests, fostering growth and success for all learners. Providing various options and activities, such as engaging science experiments, culturally immersive projects, and interactive thematic studies, allows students to explore subjects in ways that resonate with them individually.

One idea for further learning that I plan on doing involves incorporating technology-based platforms to enhance differentiated instruction. Platforms such as interactive educational apps, virtual reality experiences, or online collaborative tools can provide additional avenues for students to engage with the material, catering to different learning styles and preferences. Picardo (2017) stated that "in the school context, technology enables us to focus on smart work, instead of hard work, and challenges us to be open to doing things in novel ways, so long as the outcomes justify the application of technology to a particular aspect of teaching and learning" (p. 4). Educators can continue innovating and adapting teaching strategies to enrich their students' learning experiences and foster a lifelong love for learning.

References

Casteneda, R. (2012). ¿Qué es la Instrucción Diferenciada? https://youtu.be/bApuBiitL8Q?si=Xporap8IjUyYOg6r

Picardo, J., Findlater, S., Bloomsbury CPD Library, (2017). Using Technology in the Classroom.

Tomlinson, C. A. (2001). How to differentiate instruction in mixed-ability classrooms. Alexandria, Va: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Unit 7 Blog: Tiered Lessons and Alternative Assessment

In the realm of education, the concept of tiered instruction has emerged as a powerful tool for catering to the diverse needs of learners. Specifically tailored to address varying levels of understanding and abilities, tiered instruction offers a structured approach that can significantly benefit early childhood learners. Tiered instruction creates a dynamic learning environment that engages, challenges, and grows by adapting educational content and activities to meet each child's needs. This blog post delves into alternative assessments in early childhood education, exploring its benefits and implications for young learners in the context of homeschooling. "Tiered assignments refers to a way of differentiating curriculum by making the curriculum different to meet the different needs of the different students in the classroom" (Johnson).

Tiered instruction involves providing students with different levels of tasks or materials based on their readiness, interests, or learning profiles. When tied in with the assessment of students, tiered instruction can be highly effective in meeting the diverse needs of learners. Before implementing tiered instruction, assessing students to determine their current knowledge, skills, and understanding levels is essential. Ongoing assessment is also crucial to monitor student progress and determine if adjustments must be made within the tiered instruction framework.

The article "Getting to Know Young Children: Alternative Assessments in Early Childhood Education" explores and analyzes the themes of early childhood assessment, explicitly focusing on alternative education systems such as Reggio Emilia, Montessori, and Waldorf (Steiner). The article aims to understand how assessments can be redesigned to be developmentally appropriate for different ages by examining the unique assessment approaches of these alternative systems. The emphasis is on assessing children's learning as unique individuals, aligning with the National Association for the Education of Young Children's recommendations on developmentally appropriate assessment. The article highlights the importance of engagement, individualized assessment techniques such as observation, and creating carefully constructed learning environments to effectively assess children's learning patterns.

Becker et al. (2022) stated that "Assessment supports learning by providing children, teachers, and families with feedback, and is a key way in which teachers get to know and understand learners in their classrooms" (p. 913). Becker et al. further discuss authentic assessment, stating that it emphasizes the individual child. The feedback that it encourages teachers to give is often activity rather than outcome-focused, which encourages children's continued engagement with various materials rather than children being able to recite certain information. Authentic assessment in homeschooling young learners involves evaluating students' knowledge and skills in real-world contexts that reflect meaningful learning experiences. Some examples of authentic assessment used in my homeschool context with my young learners include real-life projects, which include hands-on projects that demonstrate their understanding of concepts, portfolios that showcase their artwork, photos of projects, writing samples, and any other relevant materials, and observation and documentation.

The journal article's authors argue that alternative education systems, such as Reggio Emilia, Montessori, and Waldorf (Steiner) learning environments, offer valuable insights into redesigning assessments to be developmentally appropriate for children of different ages. They emphasize the importance of understanding each child's unique learning and suggest that engagement should be a key focus of assessment rather than just specific knowledge. By examining the assessment practices of these alternative systems, the authors highlight the significance of individualized assessment techniques, such as observation, in creating practical and informative assessments. The materials presented in the article support the idea of differentiated instruction. "Differentiated instruction is a teaching approach that provides a variety of learning options to accommodate differences in how students learn" (Rule & Lord, (2002). By examining alternative education systems like Reggio Emilia, Montessori, and Waldorf learning environments, the authors highlight the importance of tailoring assessments to meet the unique needs and styles of the individual child. This approach aligns with the principles of differentiated instruction, which involves adapting teaching methods, content, and assessment strategies to accommodate students' diverse learning preferences and abilities.

References

Becker, I., Rigaud, V.M., Epstein, A., (2022). Getting to Know Young Children: Alternative Assessments in Early Childhood Education. Early Childhood Education Journal. 51, 911-923. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-022-01353-y

Dr. Johnson, A. (2010). Bloom's Taxonomy to Create Tiered Instruction. https://youtu.be/anLc37a8WOE?si=bUUY9jAQRx4QBlaH

Rule, A. C., & Lord, L. H. (Eds.). (2003). Activities for differentiated instruction addressing all levels of Bloom's taxonomy and eight multiple intelligences.

Unit 8.1 Mindmap recap on Differientiated Instruction

Developing the mind map on differentiated instruction provided a valuable opportunity to organize and synthesize critical concepts related to this educational approach. Initially, I began by identifying the core components of differentiated instruction, such as individualized learning and flexible grouping. As I delved deeper into the topic, I realized the intricate balance required to cater to diverse student needs while maintaining high standards of teaching and learning. Each branch and subtopic in the mind map represented a crucial aspect of differentiated instruction, prompting thoughtful consideration of how these elements intersect and complement one another. This process deepened my understanding of the nuanced strategies involved in adapting instruction to meet the varied needs of students.

One thing that stuck with me during this learning process on differentiated instruction is working with students based on their interests. As a homeschool educator with young learners, it is essential for me to reach my students through their interests. Tomlinson (2001) stated, "Teachers who care about their students as individuals accept the difficult task of trying to identify the interest students bring to the classroom and that dynamic teachers try to create new interests in their students" (p. 53).

Creating the mind map also prompted me to reflect on the broader implications of differentiated instruction within the educational landscape. I recognized the significance of embracing student diversity and promoting inclusive practices that empower all learners to succeed. The visual representation of differentiated instruction highlighted the interconnected nature of its principles and strategies, underscoring the importance of personalized learning experiences. Through this reflective process, I gained a greater appreciation for the role of effective teaching practices in supporting student engagement, growth, and achievement. Overall, developing the mind map on differentiated instruction served as a stimulating exercise that enhanced my appreciation for the complexity and potential impact of tailored approaches to teaching and learning.

Reference

Tomlinson, C. A. (2001). How to differentiate instruction in mixed-ability classrooms. Alexandria, Va: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Applied Instruction Project Presentation

Dorothy Ghiorzo

EDU 605-Differentiated Instruction

Dr. Martha Bless

Post University

Preparing the unit study on the life cycle of a butterfly has been an enriching and transformative experience for me. The process involved:

-

Meticulously planning engaging lessons that will cater to diverse learning styles.

-

Incorporating hands-on activities such as observing live butterflies.

-

Creating visual representations of the life cycle.

By providing a variety of instructional methods, including visual aids, discussions, and experiential learning opportunities, students will deepen their understanding of metamorphosis while honing critical thinking skills. This multifaceted approach will enhance their scientific knowledge and encourage creativity, collaboration, and a deep appreciation for the natural world. This interdisciplinary approach will allow students to engage with the scientific concepts of metamorphosis while also exploring connections to language arts and art.

By guiding students through exploring this natural phenomenon, I aim to instill a sense of wonder and curiosity, encouraging them to embrace challenges and transitions with resilience and grace. By prioritizing student engagement, reflective practice, and continuous growth, I strive to inspire and empower all learners in my learning environment, promoting academic success and personal development.